When emotions shadow the essence

How many times do I have to say the same thing?

If so, you’re not alone. These moments often aren’t just about communication breakdowns; they’re signs you’ve stepped into a family pattern where emotions overshadow the message you truly want to share.

Let’s explore this together, through a story many of us can relate to.

Take this scene.

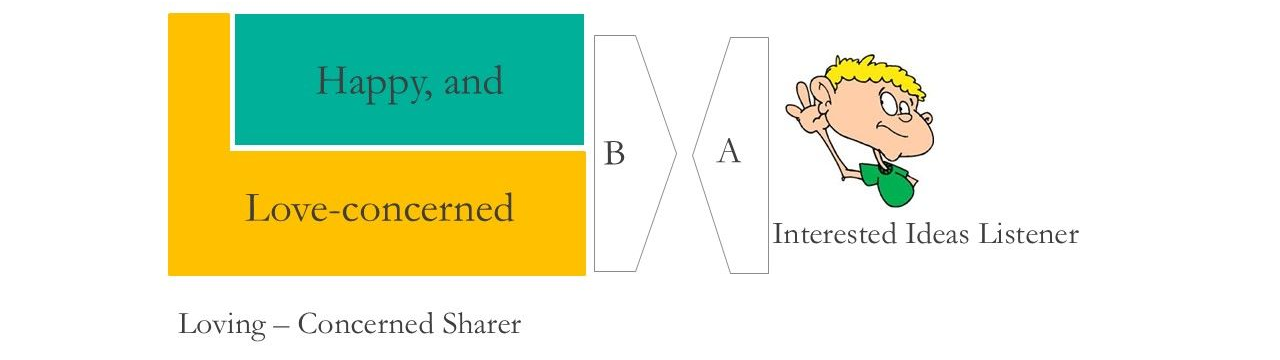

After a family dinner, 19-year-old Chloe excitedly shares her “great idea”—a camping trip overseas with her high school friend, Tina, in a foreign place known for its beauty, but also its risks. She expressed it as an enthusiastic ideas sharer.

Her amygdala fires—this is not a safe space. And it’s not the first time she’s felt this. It’s a familiar scene, replaying once again.

Without thinking, she moves to protect herself. But how?

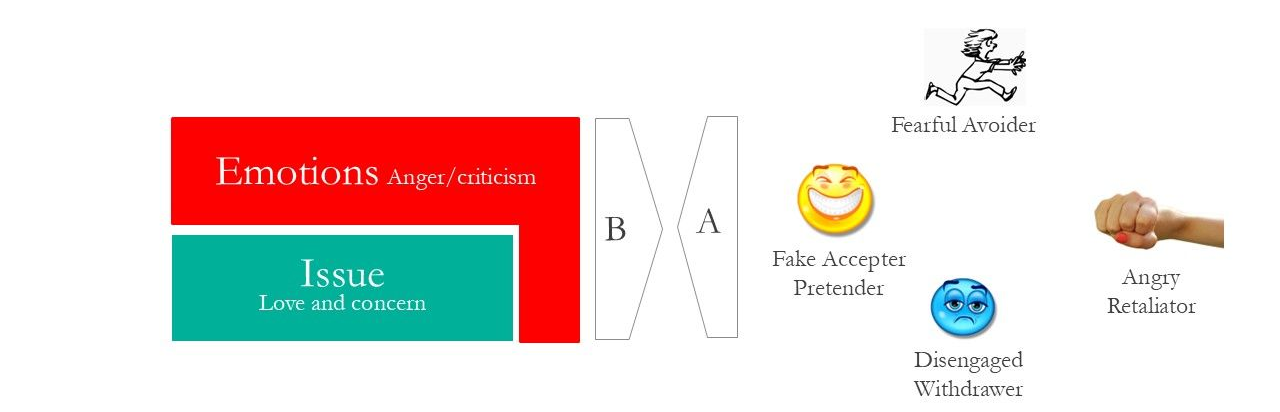

- Should she become the:

- A polite, fake accepter?

- A fearful Avoider?

- A disengaged withdrawer? Or

- An angry retaliator?

- How would you have responded?

- And what about the others in the room?

- How did they feel, and what did they do with it?

Chances are, this isn’t the first time Chloe, or anyone else in the family, has heard her dad erupt like this. It’s likely part of a long-standing family rhythm; a sort of emotional choreography that repeats so often it begins to feel familiar and inevitable. In psychodrama, Moreno described this as the Cultural Conserve, or colloquially a vicious circle, referring to the deeply ingrained patterns in family life that shape how we speak, act, and relate, much like a script handed down without conscious permission, and often through generations.

A Cultural Conserve is hard to change, and we

often wait for one person, in this case, the father, to change. But here’s the

thing: anyone in that family system can be the catalyst for change.

But it only happens when we have the energy,

spontaneity and creativity to shift the roles we play.

Back to the story

If the father and the whole family could pause for a moment, breathe, and name their feelings as they arise, they might have a chance to gain insight and step off that well-worn path. To create a new one.

A path where the family isn’t locked into a reaction but can open up to reflection. However, pausing and changing our ways of relating is not easy. Don’t feel bad if you can’t do it at the moment but be assured that you can participate in changing this dynamic. The frustrating and demanding thing would be if you continue repeating the same pattern without changing it. A process that may need the support of a wise friend or a professional companion.

What happened in Chloe’s family isn’t rare. It echoes in homes, workplaces, and friendships everywhere. I know, because I was that father.

I’ve seen myself in Chloe’s

father

I’ve been the one whose fear came out as frustration and was loud. However, through the honest feedback of my wife and children, the guidance of therapy, and my own ongoing, albeit fumbling, search for better ways to respond, I’ve learned, slowly, and not without setbacks, to choose differently.

And when I do slip back into old patterns, as

we all do, I’m more able to notice, pause, and if I miss the moment, to circle

back later and say, “I’m sorry.”

As you read this, I wonder if you can see yourself in any of these roles. Are you a:

- Chloe?

- Her father?

- A sibling?

- The mother?

- Or perhaps the quiet observer on the sidelines?

So, what is the way forward?

(When we respond from a grounded place, we create space for connection. But when we’re on shaky ground led by fear or judgment, we often provoke the same in return.)

When disagreement is held with care, something powerful happens: the system shifts. The energy flows differently. What once was a pattern of conflict might become a dance of dialogue.

The message of concern could stay the same, but with a different tone:

“Chloe, what a fantastic idea to celebrate your effort! May we discuss your plans? I have to admit, I’m feeling a bit scared.”This message conveys his excitement, care and concern. And in that space, perhaps, just perhaps, Chloe wouldn’t feel the need to defend or shut down. Maybe she could remain open, curious, and listening. Alternatively, if she reacts in the moment, she might consider the message later and reflect on it.

And from there, the conversation might become a place where ideas and concerns can meet, not necessarily to agree, but to feel heard.

That’s the kind of space where family patterns

can shift, one choice, one moment at a time.

How do we begin to shift these patterns?

Like a shrimp shedding its shell when it becomes too tight, when it’s a matter of life or death, we too must recognise when the structures we live within have grown too small for us. Yet, unlike shrimp, humans often develop survival mechanisms so robust that we learn to endure the unbearable and tolerate what should never be tolerated.

Chloe’s example, chosen for its simplicity as a sample, may seem to have a minor impact on any family or be so common among family members, but there are other situations that require serious attention.

As we've discussed before, everyone in a family shares some responsibility or, rather, the opportunity to engage with the system in which they live. And as Viktor Frankl said, when we cannot change the circumstances, we need to change ourselves.

Yet, in Chloe’s home, as in many families and social environments, power isn’t evenly distributed. It’s not easy for Chloe, her mum, or her siblings to stand steady in the face of their father’s anger, outbursts, or harsh judgment, and it's even harder if that man is a good provider and supportive in other circumstances.

Ideally, change begins when a father realises

the impact of his behaviour—not just the roots of it, but the way it ripples

through the lives of those around him. Often, though, he has no idea. Like so

many of us, he may reflect on his actions through the lens of his

intentions—well-meaning, loving, protective—and yet remain unaware of how his

ways of going about it may wound or confuse.

Focusing on our intentions feeds the ego: Look at how good I am. It can delay self-awareness, sidestep vulnerability, and keep us stuck in patterns we can’t even see. True insight, the kind that opens the door to change, demands humility—and that’s no easy task. It depends on personality, emotional stability, and a hard-won self-awareness that takes time and honest reflection to build.

Even for those of us in helping professions—therapists, counsellors, coaches, mentors—it’s a lifelong challenge. We’re trained to observe others, to guide and support, but turning that gaze inward is another matter entirely. Many of us, myself included, struggle to see our own blind spots, often without even realising it.

It’s a sobering truth: you can spend your life studying human behaviour and still miss what’s right in front of you. As the saying goes, the shoemaker’s children go barefoot.

This is where Feelings Allowed steps in, championing open-hearted conversations about emotions and gently guiding families toward connection, rather than conflict.

A way forward

The way forward rarely reveals itself in the heat of the moment. It can emerge later, when the dust has settled and the nervous system has had a chance to recover. Perhaps Chloe’s mum could gently approach the father, sharing what that interaction meant to her.

One of the most touching confrontations I

experienced came from my daughter, Stephanie, when she was seven years old. I

dismissed her without realising it, and she confronted me through art. I’m not

surprised she is now an art therapist. Read more about the

experience.

Learning to confront someone is no easy task; it’s

one of the hardest constructive roles we can take on. We often confuse

confrontation with conflict, but they are distinct concepts. To confront is to

place ourselves gently in front of the other, like a mirror, offering

reflections of what we see, feel, and experience in response to their

behaviour.

This is where a wise friend or professional

companion could assist Chloe’s mother in learning strategies to mirror her

partner.

Perhaps the family could sit down together with the father, finding a quiet moment when no one is drained or teetering on the edge of their emotions. Wisdom lies in choosing the right time and place when hearts are open and the nervous system is calm.

Of course, this process is not easy. It can

stir emotions long held in check, and many families find it too raw, too

confronting. As a society, we’re still learning how to hold space for such

openness. But if the family feels ready to talk, the key is to start gently, with

love at the centre.

Starting with the positive

A gentle and enriching way to begin is by naming the good we see in one another: the qualities we admire, the virtues quietly noticed but rarely voiced. This simple act softens the limbic system, our emotional brain, easing tension and allowing the rational brain to re-engage. It’s like watering the roots before tending the branches.

With this emotional ground nourished, the

family is better equipped to explore the more challenging areas. The goal isn’t

criticism, it’s connection.

And, not But

Instead, a gentle pause, followed by an "and..." signals the shift: “And there’s something about the way we’re relating that we’d like to talk about.”

Then, with gentleness and clarity, a person shares from their heart, using “I” statements:

“Dad, when you spoke to Chloe like that, this is how “I” felt…”

They’re not talking about him; they’re offering their lived experience, their hopes, and their hurt.

Beneath the words, what they’re saying is:

We love you deeply.

This way of speaking is pulling us apart.

We want to enjoy a better way of relating.

Reflection

- In Chloe’s place: How do I speak my truth when I already know it might be met with anger or dismissal? »

- As the father: What am I really trying to say beneath my tone or reaction? »

- As another family member: How can I, and how can we, step out of the old script and create space for a new kind of connection?

I hope you’ve enjoyed this topic; we’d like to hear your feedback, comments or questions.

Feel free to share it with your family and friends.