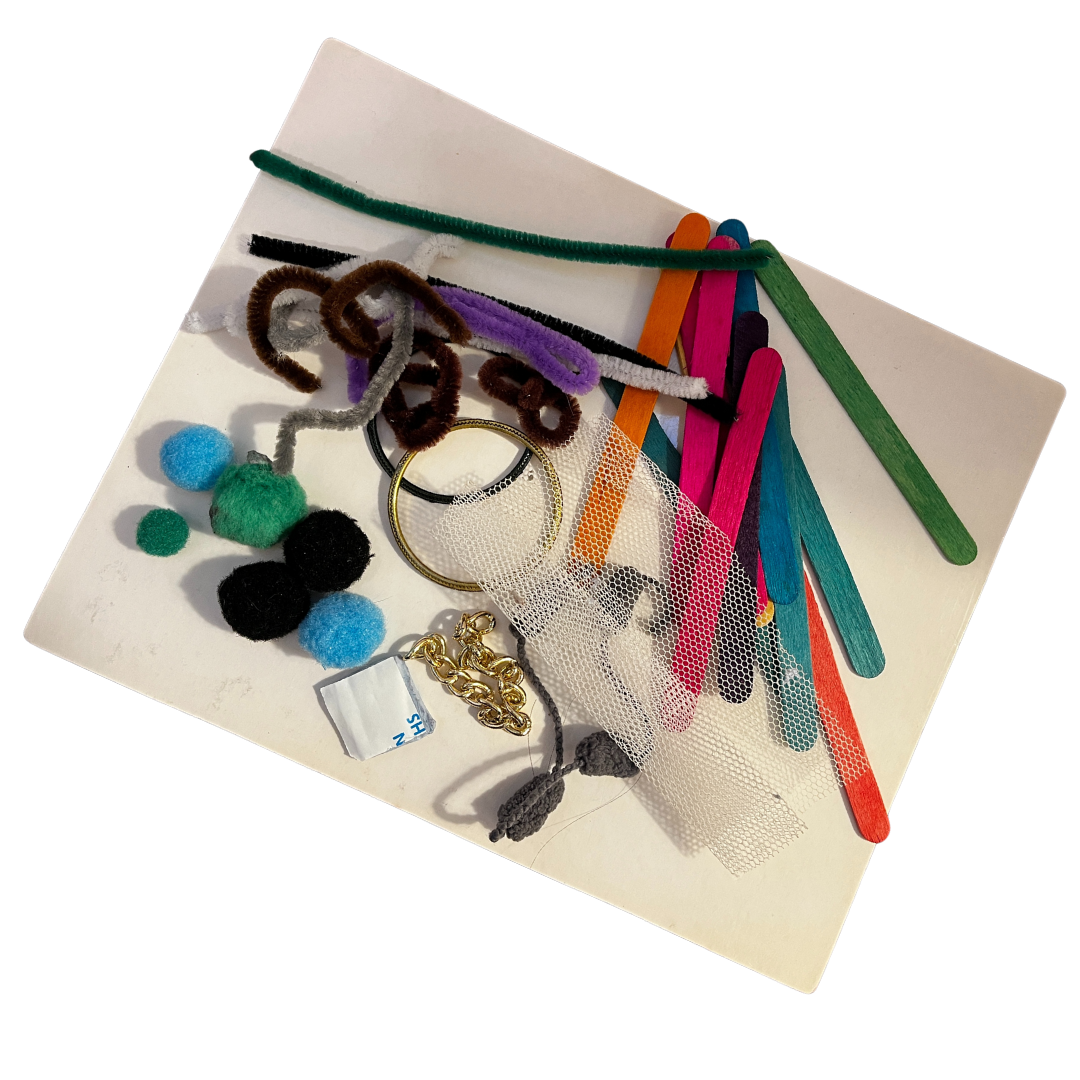

Building your kit & prop pack

When building your Play of Life kit and making it your own, we urge you to keep it simple.

“In the Play of Life methodology, it's imperative that the visual representation, within the limitations of the figurines, closely mirrors what the person is feeling or thinking.”

With this in mind, we focus more on simple figures (no animals, uniforms e.g. policemen etc.) and invite the client to show us through moulding the figure and using psychodramatic techniques such as maximisation to portray the emotion behind the action. The 3-dimensionality of the figures and the addition of props is enough to portray this. Let the seeker use their imagination to “Show Me”.

Why? Keep reading. Carlos explains the reasons why we keep it simple and our approach with a case study.

At the end of this article we provide you a list of the what to include in your prop pack.

Why? Keep reading. Carlos explains the reasons why we keep it simple and our approach with a case study.

At the end of this article we provide you a list of the what to include in your prop pack.

It's just figures on a board right?

When people first witness the Play of Life in action, they observe figures on a board and experience the remarkable effectiveness of the method. This apparent simplicity can be deceiving. It's so captivating that many individuals start incorporating figurines into their practice after participating in a brief introductory workshop or webinar on the method.

However, there's a deeper layer to using these figures, and often, it's the facilitation of these figures that holds the true power of the method, rather than the figures themselves. Therefore, it's crucial to understand that the Play of Life entails much more than simply arranging figures and props on a board. The use of these figurines (or the use of the Digital app) follows a carefully researched and systematic process conducted over three decades both by Carlos and other professionals, making it a well-established and effective approach.

Our accreditation process offers professionals a detailed, step-by-step guide on how to integrate the method into their practice. Through this process, professionals acquire a deep understanding of the specific protocol for initiating and maintaining bottom-up brain communication. By the time they receive their certification, the figurines have become an integral tool for the facilitator, and the fundamental principles of the Play of Life philosophy seamlessly lead the client toward gaining insights and taking the initial steps toward behavioural change.

However, there's a deeper layer to using these figures, and often, it's the facilitation of these figures that holds the true power of the method, rather than the figures themselves. Therefore, it's crucial to understand that the Play of Life entails much more than simply arranging figures and props on a board. The use of these figurines (or the use of the Digital app) follows a carefully researched and systematic process conducted over three decades both by Carlos and other professionals, making it a well-established and effective approach.

Our accreditation process offers professionals a detailed, step-by-step guide on how to integrate the method into their practice. Through this process, professionals acquire a deep understanding of the specific protocol for initiating and maintaining bottom-up brain communication. By the time they receive their certification, the figurines have become an integral tool for the facilitator, and the fundamental principles of the Play of Life philosophy seamlessly lead the client toward gaining insights and taking the initial steps toward behavioural change.

Play of Life kits

Students of the Play of Life often inquire about including figures or props in their toolkit. They typically envision using characters like policemen, firemen, animals (e.g., dogs, cats, horses, fairies, monsters, dragons), but they are surprised when we discourage this practice.

These props align with the Sandplay model and other projective communication, coaching, and therapy methods, which are rooted in Jungian Archetypes. While these methods are indeed valuable and profound, it's important to note that they differ from the Play of Life approach.

These props align with the Sandplay model and other projective communication, coaching, and therapy methods, which are rooted in Jungian Archetypes. While these methods are indeed valuable and profound, it's important to note that they differ from the Play of Life approach.

The Play of Life approach

In our theoretical framework, the use of characters involves a cognitive and cultural process that relies on the use of images, symbols, or pictures. The brain's frontal lobe, in a top-down manner, assesses emotions within the limbic system and associates them with a symbol to express those emotions. Identifying these characters is a product of cognitive processing.

For instance, imagine a woman who feels fear, control, disempowerment, and being put down by a male figure, such as a partner or work authority. She might say, "He's like a policeman." In response, the therapist would inquire, "Show me." The woman might use a police figure to represent her husband and another figure to depict herself, standing up in front of him to convey feeling scrutinized continuously. (Fig 1) Similarly, this approach can involve using other symbols like a firefighter for rescue, a dog for companionship or threat, or even mythical creatures like dragons or fairies.

It's crucial to understand that this mental imagery is a cognitive process for us. While it enriches verbal communication, it necessitates a rational comprehension of the underlying dynamics. The client describes their feelings, but neither the client nor the therapist can literally "see" what's being shared.

The therapist might assume they understand the situation, but in reality, they may not. The therapist's preconceived notions about what a policeman represents can inadvertently influence their interpretation of the client's representation, leading to the risk of asking biased or leading questions.

In the Play of Life methodology, it's imperative that the visual representation, within the limitations of the figurines, closely mirrors what the person is feeling or thinking.

When examining the image, the facilitator might ask, "Can you see in this picture a representation of what you're experiencing?" The client may respond, "Yes, I feel it within myself."

Facilitator (F): Can you see that in the picture?

For instance, imagine a woman who feels fear, control, disempowerment, and being put down by a male figure, such as a partner or work authority. She might say, "He's like a policeman." In response, the therapist would inquire, "Show me." The woman might use a police figure to represent her husband and another figure to depict herself, standing up in front of him to convey feeling scrutinized continuously. (Fig 1) Similarly, this approach can involve using other symbols like a firefighter for rescue, a dog for companionship or threat, or even mythical creatures like dragons or fairies.

It's crucial to understand that this mental imagery is a cognitive process for us. While it enriches verbal communication, it necessitates a rational comprehension of the underlying dynamics. The client describes their feelings, but neither the client nor the therapist can literally "see" what's being shared.

The therapist might assume they understand the situation, but in reality, they may not. The therapist's preconceived notions about what a policeman represents can inadvertently influence their interpretation of the client's representation, leading to the risk of asking biased or leading questions.

In the Play of Life methodology, it's imperative that the visual representation, within the limitations of the figurines, closely mirrors what the person is feeling or thinking.

When examining the image, the facilitator might ask, "Can you see in this picture a representation of what you're experiencing?" The client may respond, "Yes, I feel it within myself."

Facilitator (F): Can you see that in the picture?

Client (C): Not really

F: Using your two hands, change your position to demonstrate, as much as you can, how do you feel. (After the client makes the change),

F: from that position, how do you perceive the other person (they don’t say the policeman). You can change the figure if you wish. (Fig 2)

In this case, the client and the practitioner can better “see” what is happening in this dynamic.

In this case, the client and the practitioner can better “see” what is happening in this dynamic.

This is a double phenomenological experience. The client experiences the dynamics projecting themselves into the image, their role or the other, and observing from a distance.

This is a limbic picture, a representation of the core emotion and relational dynamics. The practitioner is less prone to project their contents into the image.

The process of naming, using active role theory, emotions and actions of both, and processing the image is rational. In this case, it has activated a bottom-up brain communication. The limbic system has informed the neocortex.

The same process applies for every processing of the image. The representation must show, as much as possible, the emotion described by the client and how they perceived the other. Don’t forget Maximisation.

Processing the image, a reminder: Psychodramatic techniques in action